Living with an animal that magnificent was a privilege, like living with great old trees. He was so big, and his anatomy was so beautiful. You could see all of his muscles and tendons ripple as he moved. He was the most impressive creature you ever saw. You just assumed he was some sort of a God.

His feet were enormous and powerful. Even as a puppy, he had these huge paws that he would spend the rest of his life trying to be proportionate with, like certain trees that have full-grown leaves even as spindly saplings. When he reached maturity, he still really never caught-up with his feet.

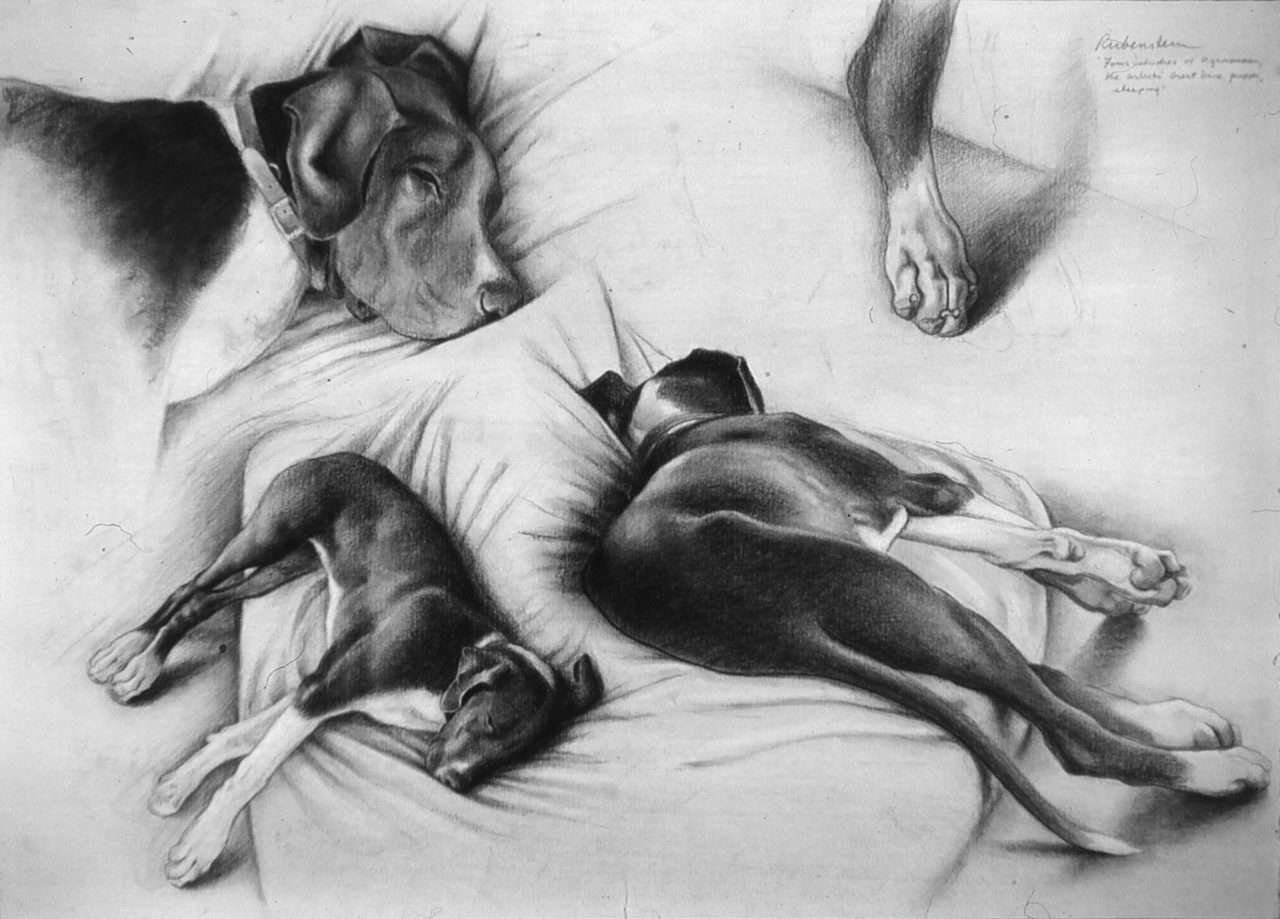

These drawings of Agamemnon embody his essential physical facts; they are large and they are black and white. And because I identified him so strongly with our house, the series of drawings is firmly located within the geography of the home; porch, kitchen, library sofa. And each of these places is associated with a certain mode.

The porch, for instance, is waiting and guarding. What does it mean to have an animal wait for you? How to describe coming up the driveway and seeing Agamemnon on the porch, all tautness and suspicion, until he recognized you, and then turning into pure affection– a display delivered through muscle hard enough to bruise and saliva enough in which to drown.

Or Agamemnon, lying on the kitchen floor, against the light, so grand and saturnine, like St. Jerome’s lion. And if you lay down on the floor with him at night, you realized that despite his human scale he still inhabited a world of chair legs and the undersides of tables– was horizontal rather than vertical.

Or the beauty and absurdity of his co-opting of the library sofa. Sprawled out on the couch, he looked like a Titian Venus– so splendid, relaxed, sensuous. The way he would fold into the sofa made his weight seem so apparent. But what got me was his sheer unknowingness of his own size and place. Imagine the ridiculousness of this Great Dane, the size of a small piece of live stock, jumping up on your (his!) sofa like some small lap dog. If he had had one ounce of sense, or had any idea what he actually looked like, he would have moved himself out into the barn to live in a stall or hooked himself up to a plow and gotten to work, rather than fallen into a deeper, doggier sleep among the books and musical instruments.

What does it mean to have an animal live with you, to occupy the same house? It changes the house. Strangely, it humanizes it. Agamemnon inhabited our house so visibly. He became associated with certain spaces, wore certain paths in the rugs, claimed certain territories as his own. He was our Lares and Penates, the guardian of our storeroom and hearth, the beneficent spirit of our ancestors.

I sketched and made drawings of Agamemnon ever since he was a puppy. He particularly fascinated me because his structure was so clear and his anatomy was so powerful. I have studied the human figure my whole life, including four years of anatomical dissections. I teach figure drawing and artistic anatomy, so I am always taken with visible structure and movement. Great Danes are shorthaired dogs, very muscular, with little subcutaneous body fat, so they are a marvel to watch and draw. His paws were particularly large and powerful, with extremely clear form.

I did not start this particular series of large-scale drawings in earnest, however, until we had to give him up this past summer. At that point, I started to draw him obsessively. So in a sense, the series is highly elegiac– a tribute to his remembered presence, a testament to the loss of that presence, but also a study of an absolutely marvelous creature that I admired tremendously and that I thought was very beautiful.

As I said, I have drawn the human figure my whole life, but apart from some casual sketching of various family pets, this is the first time I have ever done a serious body of work relating to an animal. Agamemnon was very large- almost 170 pounds– and black and white, so I wanted the drawings also to be black and white and very large. It was very important to me that these drawings be honest and powerful. It is a tough thing to work from a subject like a pet that has so often been treated in a sentimental or saccharine fashion. Of course I wanted the drawings to be filled with empathy, but not be romanticized or cloying. So in order to avoid this, I chose to do them in wax resist, which is a very raw and physical way to work.

Wax resist is a fascinating mixed media drawing technique, utilizing pencil wax, ink, various types of charcoal, conte and pastel. I learned it and adapted it for my own purposes from my friend David Dodge Lewis, a professor at Hampden-Sydney College down in Virginia. David is a brilliant artist and draftsman, and he developed this technique throughout his career, and was able to teach it to me over a period of years.

Wax resist combines both wet and dry applications, is capable of barely controllable explosions as well as great precision and subtlety, depending on which one you want to emphasize. As a technique, it blurs distinctions between painting and drawing, looseness and tightness, sculptural form and atmosphere. The process is tricky in that you have to plot out your moves ahead of time and hope that the drawing doesn’t get you in checkmate.

Common canning wax (Gulf wax found in the supermarket) cut from the block is used as a resist to an ink wash, much as a watercolorist might use a frisket as a resist to subsequent color washes, except that the wax remains a beautiful and integral part of the drawing. I execute these drawings on Lenox 100, a thin but very sturdy printmaking/drawing paper that can take a fair amount of abuse.

I hope that the series is able to recreate the physical presence of this animal, and to express my own awe and wonder about him. I wanted to surround the viewer with life size images of Agamemnon, so you could feel what it would be like to share your life with such a creature. Much like Wallace Stevens’ poem “Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird”, I wanted each drawing to give you another glimpse into the life of the dog, and each subsequent drawing changes your relationship to him as well. For instance, in the series, I am constantly changing the horizon line– some of the drawings are done from above looking down, while others are from much more on his own level. These changing viewpoints express different feelings of intimacy.

I realize also that I was at a point in things where I wanted to make a major push with the wax resist drawing and was sort of waiting for the right subject. My life situation with Agamemnon provided me with just the right opportunity. It has always been my belief that the finest drawings comprise an indissoluble union between subject and means employed, and this seemed to me like a perfect marriage.