When I lived in Richmond, Virginia, we often spent the summers on the Northern Neck, a long spit of land bounded by the Potomac River to the North and the Rappahannock to the South. Initially, I found it an unprepossessing area, patch-worked together by the relatively poor truck farms of the locals and vacation homes for the wealthy gentry from Richmond and Washington, DC. My first impressions of the area were not favorable; I found the brackish land to be too flat, too monotonous, too scrubby.

Abandoned House, Edwardsville, Virginia

oil on linen, 40” x 57”, 1987-8

“Left to its own devices, nature will not hesitate to crumble our roads, claw down our buildings, push wild vines through our walls and return every other feature of our carefully plotted geometric world to primal chaos. Nature’s way is to corrode, melt, soften, stain and chew the works of man. And eventually it will win. Eventually we will find ourselves too worn out to resist its destructive centrifugal forces; we will grow weary of repairing roofs and balconies, we will long for sleep, the lights will dim, and the weeds will be left to spread their cancerous tentacles unchecked”

-Alain de Botton, The Architecture of Happiness

One thing that caught my attention, however, were a number of old farm houses that had been abandoned and left to collapse in the middle of their respective farmlands. The demographics of the area were such that when the farmer’s children grew up, they moved off to the cities, leaving no one to work the farms. And when the farmers themselves died, the houses were left to fall apart and litter the landscape like wooden carcasses.

I remembered Kenneth Clark’s idea that landscape painting, in Clark’s view, was supposed to engender a “sense of well-being”—a peaceful, life-enhancing sense that God’s in his Kingdom and all’s right on earth. Well these houses did no such thing. They gave off a tragic, deathly sense of being far from well that I found extremely moving.

Abandoned House, Irvington, Virginia

oil on linen, 18” x 28”, 1988

This house was in a fairly early stage of deterioration when I first came upon it. Someone had come along and at least made the effort—however crudely—to board up the windows. Because of this and because of the flat expanse of unbroken space on the main part of the house, it seemed like a ‘blind’ house to me somehow. The relationship between the interior and the exterior, such an important part of most houses, was completely shut off.

I have frequently thought of the relationship between houses and people. The house is a fertile metaphor for many human qualities. Firstly, they remind us of our own bodies. They are freestanding and autonomous, with areas around them (lawns, yards, plazas) that act much like our own ‘body boundaries’. Children pick up on this similarity immediately, when they draw the facades of houses like faces, with window ‘eyes’ and a mouth-like front door. Like people, houses have most of the important features on the front; the backs tend to be plainer and are reserved for the removal of trash. By extension, houses also remind us of our families, as in the “House of Atreus”, or the general concept of ‘household’. They stand in for our communities when we build a Court House, and for our government, enough so that we appoint a House of Representatives. Lincoln understood the power of this metaphor in reference to how the question of slavery was dividing the country by saying, “A house divided against itself cannot stand”.

These abandoned houses made me think of how hard we constantly have to fight against entropy and disintegration. Any homeowner knows this; something is always breaking and in need of repair. And any aging person can tell you the same thing, as visits to the doctor and the pharmacy become increasing parts of life. These houses reminded me that life is a constant struggle, and of what it takes to stay healthy and functional.

The abandoned houses that I came across were in very different stages of disintegration. Some had merely lost windows and doors and had sagging rooflines. Others were starting to completely come undone; pieces of the roof had fallen off and vines were ripping apart the clapboard.

Abandoned House on A Hill, Northumberland County, Virginia

oil on linen, 46” x 68”, 1988–9

I painted Abandoned House on a Hill completely outdoors. It was one of the largest canvases that I ever painted plein-air, and it turned into a wrestling match from the very beginning. I didn’t realize the extent to which the canvas would become a sail, catch wind and try to fly away. Once, I turned around to get something out of my bag and a strong gust of wind came up and carried the easel away. I ended up having to get stakes and guy wires and tie it down each day. Of course, as the sun moves, you have to keep turning the easel, which entailed pulling up the stakes each time.

I once decided to enter one of these houses. As I hacked my way through the foliage, I found what used to be the front door of the house. I stepped on the doorsill and the whole house started humming, like the string section of a symphony orchestra warming up. Termites were buzzing and making the whole house move. Snakes slithered, birds darted, mice scurried; the entire animal world had taken up residence even as the humans had departed. If a house had been abandoned for a very long time, it became completely engulfed by vegetation. Some, so much so, that I barely knew that there was a house within the verdant mass. In these last stages of abandonment, it was as if the earth were starting to reclaim the house and to take it back into its arms.

In this case, the house was lost. But the fields to the right were lush and abundant, still farmed and productively organized into rows. It was the contrast between these two things- loss and abundance- that I found so poignant.

These houses are powerful statements about the human condition and meditations on the passage of time and the struggle to remain whole. But one couldn’t possibly live in them. Ultimately, I think that Clark is correct, that landscape painting has the capacity to impart a ‘sense of well-being’ unlike any other genre. Woodley, the 19th-century Maryland plantation house that I live and work in, is one of those magical places that does just that.

Woodley, Summer, Dawn

oil on linen, 52” x 38”, 2012

More than any place I know, Woodley imparts a ‘sense of well-being’. By this I mean a place that is peaceful, calm, centered; that is ‘life enhancing’. It has beautiful light and spaces that invite you to enter and walk around. It is a place that reminds you of people you love, or would like to get to know.

Woodley, Sunlight I

oil on linen, 46” x 34”, 2009-12

Supposedly, on his deathbed, Turner asked to be taken outside so that he could ‘see the light one more time’. It is no accident that light has been a central concern of almost every religion. Light reveals the world to us, and all paintings are ultimately about light. One of the hardest things in the world is to stop thinking about objects, and really focus on space and light. One of the best ways to do this is to paint the interior of an empty room.

Woodley, Sunlight II

oil on linen, 52”x44”, 2010-12

I have been chasing this sunbeam for several years now. As with the Boxwoods, the light is only in place for about 20 minutes at a time. I worked on several paintings in this series at the same time. Not only does the light change dramatically during any given day, it is very different from season to season. The summer light is much warmer, while the winter light is starker and colder. For inspiration and perseverance, I think of Monet working away on his stack of canvases in his rooms across the street from Rouen Cathedral.

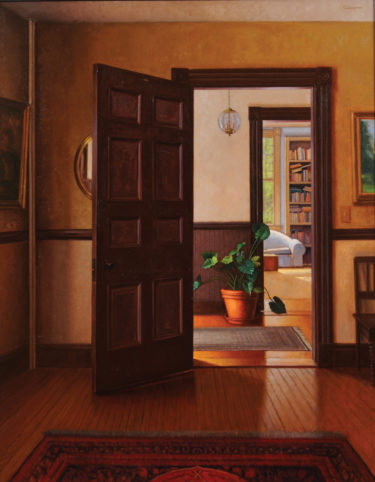

The house immediately makes you feel at peace. It has strong bones, grand without being in the slightest way pretentious. Its forty-seven windows let in light from every direction, and help the rich polished wood-paneling from feeling too dark.(Illustrations #6 and #7, “Woodley, Sunlight I and II”). There is a marvelous flow as you walk through the house. This is created because each room has at least two doors in it, so you never have to turn around and exit a room the same way you entered it. Rooms unfold onto rooms- there are no obstacles, no dead ends.

Woodley Interior; View of the Library

oil on linen, 48” x 38”, 2009

There is a marvelous flow as you walk through my house. This is created, in part, because each room has at least two doors in it, so you never have to turn around and leave a room the same way you entered. Rooms unfold onto rooms- there are no obstacles, no dead ends.

Likewise, the grounds are lovely and spacious, a haven within which we host dozens of birds, rabbits, fox, and deer. The grounds still has the original smokehouse as well as a set of magnificent 18th century boxwoods that originally acted as a natural gate for a carriage path.

Boxwoods, Woodley

oil on linen, 30” x 42”, 2008

I woke up very early each morning the summer I was working on this painting, and was out there by 6:00 AM. As the sun rose, the light started to clip the top of the boxwoods. I wanted to preserve that early raking light, which was only like that for twenty minutes at most. I then had to keep the subject in my memory and when that failed, work on other parts of the canvas.

These two subjects, the ‘abandoned house’ and the ‘house of well being’, have acted as emotional poles- metaphors for loss and abundance- between which I have oscillated, depending on the circumstances of my life. Because I have been battling serious illness in recent years, I have gone back to identifying the house with the ravaged body- the body that is falling apart and can no longer function. The major painting I worked on when I could work was of a set of abandoned row houses. It is a very moving sight, these houses which used to be homes to real families, now breaking apart, sagging, splitting, doors and windows all smashed and useless.

Illness and surgery tell you what it feels like to be broken- to have the normal barriers between inside and outside violated. Structures like these remind us that it is work to remain upright everyday, to stand up in the face of gravity, sickness and entropy. Jamie Wyeth said that even a bale of hay could be a self-portrait, if it was painted with feeling and conviction. So can a house.

Abandoned Row Houses, Richmond, Virginia

oil on linen, 38” x 68”, 2011-13

In this painting, I started in the top corner of the central roof, where I could be close to the green trash trees and vines, the delicate Prussian blue sky and the rich brick red of the buildings themselves. This trio established the whole key of the painting right at the beginning. I worked as much alla prima possible, but there are some areas that have as many as six or seven layers (see “Lesson). The tops of the buildings have an ornamental entablature that has this wonderfully elusive color, some kind of faded gray, green, silver note- I don’t know what it was originally, but time and the weather have given it a ghostly patina that is so elusive to capture.